On January 23 1973 one of the most dramatic eruptions in recent Icelandic history began when a long lava spewing fissure opened up along the eastern shore of Heimaey island. Not only did the eruption take place inside an urban area, one of the most important fishing towns in Iceland, it took Icelanders by complete surprise.

The entire population of the island was evacuated during the eruption, and today, 45 years later, the population of Vestmannaeyjar has yet to recover from the eruption. Meanwhile the lava added 2.2 km2 (0.85 sq mi) to the island, growing it from 11.2 km2 (4.3 sq mi) to 13.14 km2 (5.2 sq mi).

Active volcano and important fishing harbour

Vestmannaeyjar islands are an archipelago of 15 islands and some 30 skerries and volcanic stacks just off the south coast of Iceland. The islands are part of an active volcanic system. They have been formed in 70-80 different eruptions during the past 15,000 years. The most recent eruption prior to the Heimaey eruption took place in 1963. This eruption created the southernmost island off the coast of Iceland, Surtsey.

Heimaey island, the largest of the Vestmannaeyjar islands, has long been home to a prosperous fishing industry. In the early 20th century the town became one of the centers of the trawling industry. 8.5% of the total fish catch of Iceland was landed in Vestmannaeyjar on the eve of the 1973 eruption.

No advance warning

The inhabitants of Vestmannaeyjar were all sound asleep when the eruption began shortly after two in the morning of January 23 1973. The eruption came as a surprise, as scientists had failed to notice any warning signs. Þorsteinn Vilhjálmsson, professor emeritus in geophysics at the University of Iceland argues that modern day monitoring of volcanic activity should provide warnings several days in advance.

Eye witnesses who saw the eruption begin first thought all houses in the eastern part of town had caught fire, but then realized that they were witnessing the earth opening and lava spewed dozens of meters up into the air. People who lived in houses closest to the fissure described a slowly rising noise prior to the eruption. The noise then turned into a thundering din, resembling a jet engine.

The police was alerted immediately and emergency sirens were sounded to alert the population. Within minutes all 5,273 inhabitants were awake.

A wall of fire

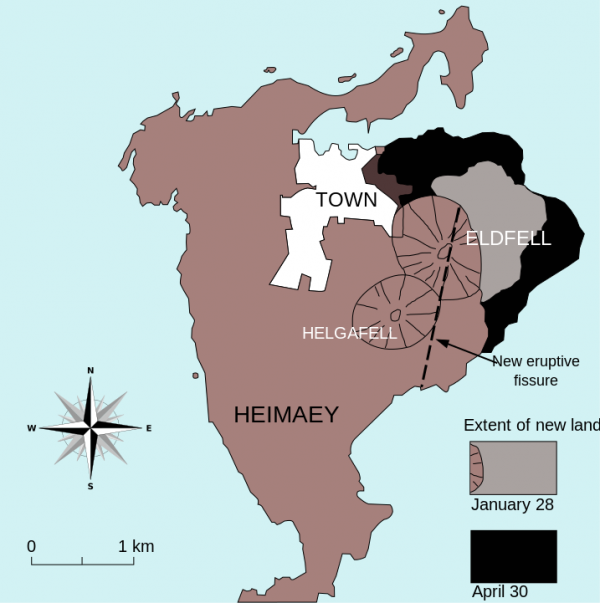

The eruption took place along a 1.6 km (1 mi) long North-South fissure with 30-40 different craters, which extended along the eastern coast of Heimaey island. The northern edge of the fissure extended right up to the harbour of Vestmannaeyjar town, runing south along the edge of the town.

Lava spewed from this fissure as high as 600 m (1,970 ft) up into the air from these craters, and individual lava bombs were catapulted up to 2,500 m (1.6 miles) up into the air. The eruption quickly concentrated in the center of the fissure, with the two opposite ends closing up relatively quickly. The lava and tepthra from the central craters gradually piled up a new mountain, the small mount Eldfell which rises 200 m (660 ft) above sea level.

Saving lives and rescuing the town

Panic gripped people who realized the eruption could easily swallow the town. People also feared for their lives, as people realized that the rapidly advancing lava was not the only threat, but also poisonous gases. The inhabitants flocked down to the harbour where fishing vessels immediately started ferrying people to the mainland. Nearly all inhabitants were evacuated in the first day. 200-300 stayed behind to try to save valuables from businesses and people's homes. Members of ICE-SAR from the mainland quickly joined the local volunteers.

Dozens of houses were destroyed. Many were swallowed by the lava, others were set on fire when they were hit by bombs of glowing magma. But houses which were out of reach of the magma were also in danger as thick layers of ash, tepthra and volcanic slag were deposited on the town, causing roofs to cave in. One of the most important tasks quickly became to shovel ash and slag from the roofs of houses.

By the end of January the tephra and ash had covered most of the island, reaching up to 5 m (16 ft) in places. Despite the best efforts of the volunteers hundreds of houses were destroyed. Out of the 1,350 houses in Vestmannaeyjar 417 were swallowed by the lava, and another 400 were damaged or destroyed by tephra and slag.

Fighting the volcano

Working hard to save the town the volunteers built walls and blocked streets in an effort to divert the flow of the lava away from the town. Water was also pumped onto the lava to help solidify it and slow the advance of the lava flow. Water had previously been used to cool down and slow advancing lava flows in Hawaii and at Mt. Etna, but these had been relatively small scale. The operation in Heimaey was therefore a completely unique: The first attempt by humans to mount a full scale defense against a volcanic eruption.

Volunteers worked laying pipes across the active lava field pumping water down into the lava to slow down the advancing flow. The teams laying the pipes were called The Suicide Squad: Working on top of an active lava flow as much as 130 m (430 ft) was correctly seen as suicidal! Although a few of these volunteers suffered minor burns, none sustained serious injuries and none of the volunteers died.

These efforts were somewhat successful, but it was only after 32 high powered pumps were brought in from the US at the end of March that the advance of the lava into town was stopped. However, ultimately the greatest threat to the town was not that the lava might swallow homes and businesses, but that it would close the town's harbour: If the harbour was destroyed the fishing industry, the lifeblood of the community, would also be destroyed.

Defending the harbour

On March 9 the lava flow began to push dangerously close to the harbour's mouth, threatening to close the harbour off from the sea. The rescue operations now focused on protecting the harbour as boats and ships outfitted with water cannons sprayed the lava heading towards the harbor in an attempt to stop its advance.

These efforts proved remarkably successful, as the flow of lava toward the harbour slowed down and ultimately stopped. Rather than destroying the harbour the lava created a kind of new powerful breakwater, protecting the harbour from storms. When the pumping of water to cool the flow of lava finally stopped on July 10 it was estimated that some 8 million cubic yards of seawater had been pumped over the lava.

Life returns to normal

The eruption continued for a total of five months, coming to an end on July 3. The total volume of lava and tepthra emitted during the five months has been estimated at about 0.25 cubic kilometers (0.06 cubic miles). In addition to dumping a thick layer of tepthra over large parts of the island the eruption added 2.5 square kilometers (1 sq mi) of new land, expanding the surface of Heimaey by nearly 20%.

People began returning to their homes in August. By mid September 1,200 people had returned to the islands. Many decided not to return, either because their homes had bee destroyed or because they had found work on the mainland. Still today the population of Vestmananeyjar has not recovered to its pre-eruption peak of 5,273. Today some 4,200 people live in the town of Vestmannaeyjar.

On January 23 1973 one of the most dramatic eruptions in recent Icelandic history began when a long lava spewing fissure opened up along the eastern shore of Heimaey island. Not only did the eruption take place inside an urban area, one of the most important fishing towns in Iceland, it took Icelanders by complete surprise.

The entire population of the island was evacuated during the eruption, and today, 45 years later, the population of Vestmannaeyjar has yet to recover from the eruption. Meanwhile the lava added 2.2 km2 (0.85 sq mi) to the island, growing it from 11.2 km2 (4.3 sq mi) to 13.14 km2 (5.2 sq mi).

Active volcano and important fishing harbour

Vestmannaeyjar islands are an archipelago of 15 islands and some 30 skerries and volcanic stacks just off the south coast of Iceland. The islands are part of an active volcanic system. They have been formed in 70-80 different eruptions during the past 15,000 years. The most recent eruption prior to the Heimaey eruption took place in 1963. This eruption created the southernmost island off the coast of Iceland, Surtsey.

Heimaey island, the largest of the Vestmannaeyjar islands, has long been home to a prosperous fishing industry. In the early 20th century the town became one of the centers of the trawling industry. 8.5% of the total fish catch of Iceland was landed in Vestmannaeyjar on the eve of the 1973 eruption.

No advance warning

The inhabitants of Vestmannaeyjar were all sound asleep when the eruption began shortly after two in the morning of January 23 1973. The eruption came as a surprise, as scientists had failed to notice any warning signs. Þorsteinn Vilhjálmsson, professor emeritus in geophysics at the University of Iceland argues that modern day monitoring of volcanic activity should provide warnings several days in advance.

Eye witnesses who saw the eruption begin first thought all houses in the eastern part of town had caught fire, but then realized that they were witnessing the earth opening and lava spewed dozens of meters up into the air. People who lived in houses closest to the fissure described a slowly rising noise prior to the eruption. The noise then turned into a thundering din, resembling a jet engine.

The police was alerted immediately and emergency sirens were sounded to alert the population. Within minutes all 5,273 inhabitants were awake.

A wall of fire

The eruption took place along a 1.6 km (1 mi) long North-South fissure with 30-40 different craters, which extended along the eastern coast of Heimaey island. The northern edge of the fissure extended right up to the harbour of Vestmannaeyjar town, runing south along the edge of the town.

Lava spewed from this fissure as high as 600 m (1,970 ft) up into the air from these craters, and individual lava bombs were catapulted up to 2,500 m (1.6 miles) up into the air. The eruption quickly concentrated in the center of the fissure, with the two opposite ends closing up relatively quickly. The lava and tepthra from the central craters gradually piled up a new mountain, the small mount Eldfell which rises 200 m (660 ft) above sea level.

Saving lives and rescuing the town

Panic gripped people who realized the eruption could easily swallow the town. People also feared for their lives, as people realized that the rapidly advancing lava was not the only threat, but also poisonous gases. The inhabitants flocked down to the harbour where fishing vessels immediately started ferrying people to the mainland. Nearly all inhabitants were evacuated in the first day. 200-300 stayed behind to try to save valuables from businesses and people's homes. Members of ICE-SAR from the mainland quickly joined the local volunteers.

Dozens of houses were destroyed. Many were swallowed by the lava, others were set on fire when they were hit by bombs of glowing magma. But houses which were out of reach of the magma were also in danger as thick layers of ash, tepthra and volcanic slag were deposited on the town, causing roofs to cave in. One of the most important tasks quickly became to shovel ash and slag from the roofs of houses.

By the end of January the tephra and ash had covered most of the island, reaching up to 5 m (16 ft) in places. Despite the best efforts of the volunteers hundreds of houses were destroyed. Out of the 1,350 houses in Vestmannaeyjar 417 were swallowed by the lava, and another 400 were damaged or destroyed by tephra and slag.

Fighting the volcano

Working hard to save the town the volunteers built walls and blocked streets in an effort to divert the flow of the lava away from the town. Water was also pumped onto the lava to help solidify it and slow the advance of the lava flow. Water had previously been used to cool down and slow advancing lava flows in Hawaii and at Mt. Etna, but these had been relatively small scale. The operation in Heimaey was therefore a completely unique: The first attempt by humans to mount a full scale defense against a volcanic eruption.

Volunteers worked laying pipes across the active lava field pumping water down into the lava to slow down the advancing flow. The teams laying the pipes were called The Suicide Squad: Working on top of an active lava flow as much as 130 m (430 ft) was correctly seen as suicidal! Although a few of these volunteers suffered minor burns, none sustained serious injuries and none of the volunteers died.

These efforts were somewhat successful, but it was only after 32 high powered pumps were brought in from the US at the end of March that the advance of the lava into town was stopped. However, ultimately the greatest threat to the town was not that the lava might swallow homes and businesses, but that it would close the town's harbour: If the harbour was destroyed the fishing industry, the lifeblood of the community, would also be destroyed.

Defending the harbour

On March 9 the lava flow began to push dangerously close to the harbour's mouth, threatening to close the harbour off from the sea. The rescue operations now focused on protecting the harbour as boats and ships outfitted with water cannons sprayed the lava heading towards the harbor in an attempt to stop its advance.

These efforts proved remarkably successful, as the flow of lava toward the harbour slowed down and ultimately stopped. Rather than destroying the harbour the lava created a kind of new powerful breakwater, protecting the harbour from storms. When the pumping of water to cool the flow of lava finally stopped on July 10 it was estimated that some 8 million cubic yards of seawater had been pumped over the lava.

Life returns to normal

The eruption continued for a total of five months, coming to an end on July 3. The total volume of lava and tepthra emitted during the five months has been estimated at about 0.25 cubic kilometers (0.06 cubic miles). In addition to dumping a thick layer of tepthra over large parts of the island the eruption added 2.5 square kilometers (1 sq mi) of new land, expanding the surface of Heimaey by nearly 20%.

People began returning to their homes in August. By mid September 1,200 people had returned to the islands. Many decided not to return, either because their homes had bee destroyed or because they had found work on the mainland. Still today the population of Vestmananeyjar has not recovered to its pre-eruption peak of 5,273. Today some 4,200 people live in the town of Vestmannaeyjar.