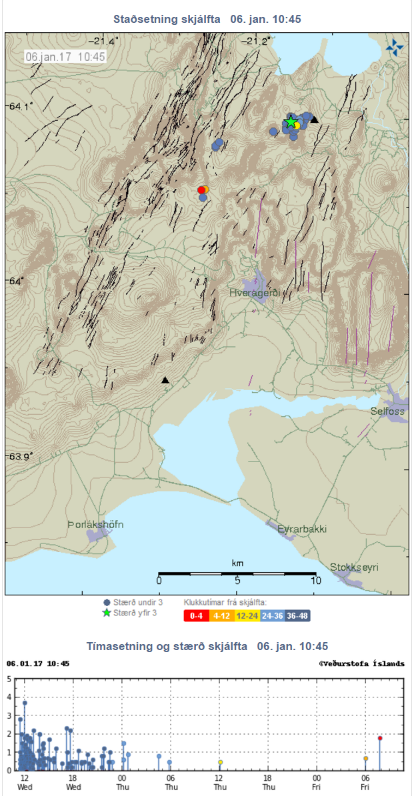

The earthquake swarm which started early Wednesday morning south of Þingvallavatn lake seems to be over. More than 170 separate quakes were detected by the Icelandic Meteorological Office during the episode, the most powerful a 3.7 magnitude quake which was felt in the metropolitan area and large parts of South and West Iceland. Two of Iceland's most powerful volcanoes joined in with two powerful quakes.

Read more: The powerful earthquakes in Iceland's largest volcanoes and S. of Þingvellir not connected

According to data from the IMO the last quake in the area took place at 7:45 this morning. This quake took place further to the south than the epicenter of the swarm which started on Wednesday.

The quakes are most likely connected to friction caused by the drifting of the tectonic plates which move in opposite direction at the rate of 2cm (0.8 in) annually.

The entire Þingvellir region is located in a rift valley created by the drifting apart of the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates. The plate boundary runs through Iceland. In Reykjanes peninsula, the plates inch past each other at a constant rate, but at Þingvellir, they move in opposite directions, breaking apart. This causes the land between them to subside.

The 7.7 km (4.8 mile) long Almannagjá gorge on the west edge of the Þingvellir National Park, where the Viking age wcommonwealth parliament Alþingi met, marks the western edge of the valley. Heiðagjá gorge on the east edge of Þingvellir marks the eastern edge of the rift valley.

The valley has subsided by at least 4 meters (12 ft) since Iceland was settled. As the entire rift valley has subsided the shore of the lake has moved further to the North. At the same time the valley edges have drifted apart. The expansion of the valley since Iceland was settled is somewhere around 8.5 meters (28 ft).

The movement of the tectonic plates is not constant in Þingvellir, as it is in Reykjanes peninsula. Here the movement takes place in busts, as tensions build up and the movement taking place in bursts of major earthquakes and subsiding of the valley.

The most recent burst of activity swept over Þingvellir in spring 1789. The valley subsided 1-2 meters (3-6 ft) during this episode. Periodically the valley has then been filled with lava in eruptions of nearby volcanoes. The last eruption took place 2000 years ago.

The entire area is still highly active geologically, as can be seen from this week's earthquakes, and the question is not whether, but when, the next major eruption takes place.

The earthquake swarm which started early Wednesday morning south of Þingvallavatn lake seems to be over. More than 170 separate quakes were detected by the Icelandic Meteorological Office during the episode, the most powerful a 3.7 magnitude quake which was felt in the metropolitan area and large parts of South and West Iceland. Two of Iceland's most powerful volcanoes joined in with two powerful quakes.

Read more: The powerful earthquakes in Iceland's largest volcanoes and S. of Þingvellir not connected

According to data from the IMO the last quake in the area took place at 7:45 this morning. This quake took place further to the south than the epicenter of the swarm which started on Wednesday.

The quakes are most likely connected to friction caused by the drifting of the tectonic plates which move in opposite direction at the rate of 2cm (0.8 in) annually.

The entire Þingvellir region is located in a rift valley created by the drifting apart of the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates. The plate boundary runs through Iceland. In Reykjanes peninsula, the plates inch past each other at a constant rate, but at Þingvellir, they move in opposite directions, breaking apart. This causes the land between them to subside.

The 7.7 km (4.8 mile) long Almannagjá gorge on the west edge of the Þingvellir National Park, where the Viking age wcommonwealth parliament Alþingi met, marks the western edge of the valley. Heiðagjá gorge on the east edge of Þingvellir marks the eastern edge of the rift valley.

The valley has subsided by at least 4 meters (12 ft) since Iceland was settled. As the entire rift valley has subsided the shore of the lake has moved further to the North. At the same time the valley edges have drifted apart. The expansion of the valley since Iceland was settled is somewhere around 8.5 meters (28 ft).

The movement of the tectonic plates is not constant in Þingvellir, as it is in Reykjanes peninsula. Here the movement takes place in busts, as tensions build up and the movement taking place in bursts of major earthquakes and subsiding of the valley.

The most recent burst of activity swept over Þingvellir in spring 1789. The valley subsided 1-2 meters (3-6 ft) during this episode. Periodically the valley has then been filled with lava in eruptions of nearby volcanoes. The last eruption took place 2000 years ago.

The entire area is still highly active geologically, as can be seen from this week's earthquakes, and the question is not whether, but when, the next major eruption takes place.