In an average week Iceland's national seismic monitoring network detects around 500 earthquakes, thousands if there‘s an seismic episodes in any of the active volcanoes. The reason is that Iceland is located on top of the Atlantic ridge: As the Eurasian and North American plates drift in opposite directions, Iceland is literally being torn apart, causing constant seismic activity.

Read more: How fast is Iceland growing due to the tectonic plates drifting apart?

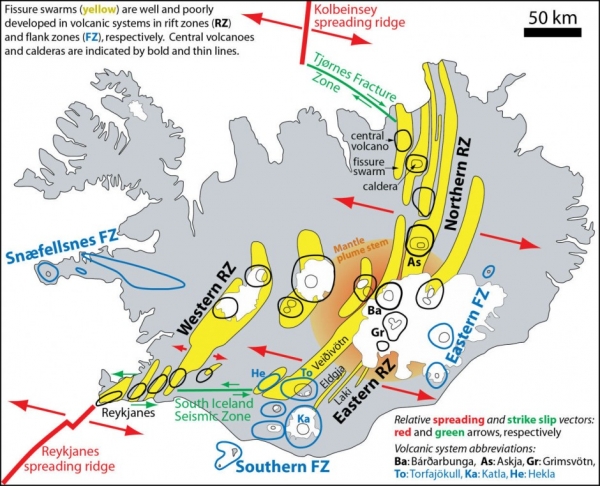

The volcanic zones are located along the boundary of the tectonic plates. They extend east from Reykjanes peninsula in the southwest where the Reykjanes ridge section of the North Atlantic ridge rises above sea level, and north-east from Mýrdalsjökull glacier in South Iceland, along the western part of Vatnajökull glacier in the Central Highlands, and then extending north into the Arctic.

Comparing maps of the volcanic zones and the seismic activity in a typical week reveals an almost perfect match, as most earthquakes take place in the active volcanic systems or in the South Iceland Seismic Zone, a transform fault which connects the two zones.

Different types of quakes

There are two main types of earthquakes in Iceland: Those caused by volcanic activity and the movement of magma, or quakes caused by the release of tension caused by the movement of the tectonic plates. Other types include quakes caused by changes in geothermal activity.

Read more: Powerful earthquake swarm south of Þingvellir over after 170 quakes: What happened?

Most of the hundreds of earthquakes detected each week are very small, and pass without people noticing. Large quakes (3+ on the Richter scale) are most common in the active volcanic systems. While a magnitude 3 quake would not be considered a major seismic event if it took place on a continental fault line, they are considered very significant when they take place in volcanoes, where they are caused by the movement of magma.

Volcanic and seismic zones

The two monster volcanoes Katla, hidden under Mýrdalsjökull glacier and Bárðarbunga, beneath Vatnajökull glacier, have been particularly active in recent years. Geologists believe both are gearing up for eruptions. Katla, which erupts once every 40-60 years is long „overdue“ for a major eruption: Its last eruption was in 1918.

Other volcanoes have also trembled in recent years, including Öræfajökull (see previous/next page) the Eldey system off the Reykjanes peninsula, mt. Hengill south of Þingvellir National Park and mt. Hekla in South Iceland.

Read more: Intense earthquakes in Grímsey highly unusual. Volcanic eruption unlikely

A second important type of earthquakes common in Iceland are fissure rifting events. Fissure swarms form at divergent plate boundaries, where the crust fractures by the pull of the tectonic plates. Fissure rifting takes place in intense rifting events which are accompanied by intrusion of magma into the crust. Such an event took place in the Tjörnes Fracture Zone off the north coast of Iceland earlier this year when thousands of quakes hit the remote Grímsey settlement.

Waiting for the big one

The other major fault zone is the South Iceland Seismic Zone, a transform fault between offset sections of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. It sits between the two volcanic zones, and is constantly being pulled in two different directions, causing tension to build up, which is then periodically released in earthquakes.

The zone has produced the most powerful earthquakes in Iceland, including what is believed to have been the most powerful quake to hit Iceland since its settlement. In 1784 a massive 7.1 magnitued earthquake caused widespread damage in South Iceland.

Quakes of this magnitude are believed to hit once every 100-150 years: The last major quake took place in 1912, which means we are currently awaiting for the big one.

Icelandic geology The volcanic zones and the fracture zones which connect them Image/IMO

In an average week Iceland's national seismic monitoring network detects around 500 earthquakes, thousands if there‘s an seismic episodes in any of the active volcanoes. The reason is that Iceland is located on top of the Atlantic ridge: As the Eurasian and North American plates drift in opposite directions, Iceland is literally being torn apart, causing constant seismic activity.

Read more: How fast is Iceland growing due to the tectonic plates drifting apart?

The volcanic zones are located along the boundary of the tectonic plates. They extend east from Reykjanes peninsula in the southwest where the Reykjanes ridge section of the North Atlantic ridge rises above sea level, and north-east from Mýrdalsjökull glacier in South Iceland, along the western part of Vatnajökull glacier in the Central Highlands, and then extending north into the Arctic.

Comparing maps of the volcanic zones and the seismic activity in a typical week reveals an almost perfect match, as most earthquakes take place in the active volcanic systems or in the South Iceland Seismic Zone, a transform fault which connects the two zones.

Different types of quakes

There are two main types of earthquakes in Iceland: Those caused by volcanic activity and the movement of magma, or quakes caused by the release of tension caused by the movement of the tectonic plates. Other types include quakes caused by changes in geothermal activity.

Read more: Powerful earthquake swarm south of Þingvellir over after 170 quakes: What happened?

Most of the hundreds of earthquakes detected each week are very small, and pass without people noticing. Large quakes (3+ on the Richter scale) are most common in the active volcanic systems. While a magnitude 3 quake would not be considered a major seismic event if it took place on a continental fault line, they are considered very significant when they take place in volcanoes, where they are caused by the movement of magma.

Volcanic and seismic zones

The two monster volcanoes Katla, hidden under Mýrdalsjökull glacier and Bárðarbunga, beneath Vatnajökull glacier, have been particularly active in recent years. Geologists believe both are gearing up for eruptions. Katla, which erupts once every 40-60 years is long „overdue“ for a major eruption: Its last eruption was in 1918.

Other volcanoes have also trembled in recent years, including Öræfajökull (see previous/next page) the Eldey system off the Reykjanes peninsula, mt. Hengill south of Þingvellir National Park and mt. Hekla in South Iceland.

Read more: Intense earthquakes in Grímsey highly unusual. Volcanic eruption unlikely

A second important type of earthquakes common in Iceland are fissure rifting events. Fissure swarms form at divergent plate boundaries, where the crust fractures by the pull of the tectonic plates. Fissure rifting takes place in intense rifting events which are accompanied by intrusion of magma into the crust. Such an event took place in the Tjörnes Fracture Zone off the north coast of Iceland earlier this year when thousands of quakes hit the remote Grímsey settlement.

Waiting for the big one

The other major fault zone is the South Iceland Seismic Zone, a transform fault between offset sections of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. It sits between the two volcanic zones, and is constantly being pulled in two different directions, causing tension to build up, which is then periodically released in earthquakes.

The zone has produced the most powerful earthquakes in Iceland, including what is believed to have been the most powerful quake to hit Iceland since its settlement. In 1784 a massive 7.1 magnitued earthquake caused widespread damage in South Iceland.

Quakes of this magnitude are believed to hit once every 100-150 years: The last major quake took place in 1912, which means we are currently awaiting for the big one.

Icelandic geology The volcanic zones and the fracture zones which connect them Image/IMO