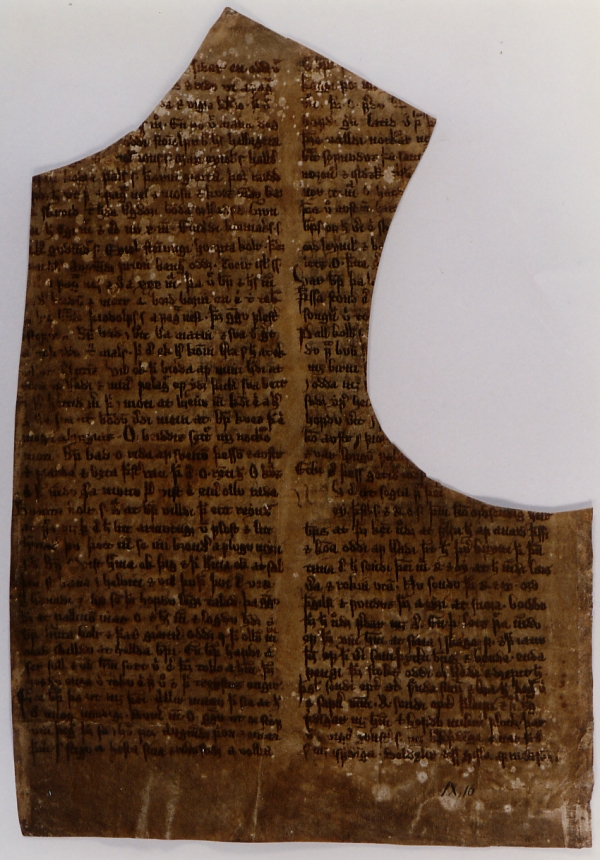

One of the oldest skin, or vellum, manuscripts in the collection of the The Árni Magnússon Institute of Icelandic Studies in Reykjavík was punctured and used as a wheat sieve by its previous owner.

Dating from around the year 1200 the manuscript, includes in addition to the text, some of the oldest drawings that have been preserved in Iceland.

But why did someone show such a historic item so much disrespect as punching holes in it and make it into a simple utensil?

In an interview with The National Broadcasting Service Guðvarður Már Gunnlaugsson, an expert at the Árni Magnússon Institute, explained that when the contents of the old manuscripts had been copied on paper (starting in the 16th century) the old skin books were deemed redundant. The skin they were made of was, however, considered quite precious and often found an afterlife in different roles. Other examples include for example insoles of shoes and patterns for clothing.

The interesting fact is that this recycling of the old books played a large part of them being preserved instead of being thrown away.

The books were made of calf skin, a very expensive material indeed. Flateyjarbók the largest medieval Icelandic manuscript, includes 225 written and illustrated vellum leaves, made from the skin of 113 calves.

Read more: Where does the Icelandic language stem from?

The Icelandic sagas were written starting in the 13th century, even though the events described took place 200 to 300 years prior.

One of the oldest skin, or vellum, manuscripts in the collection of the The Árni Magnússon Institute of Icelandic Studies in Reykjavík was punctured and used as a wheat sieve by its previous owner.

Dating from around the year 1200 the manuscript, includes in addition to the text, some of the oldest drawings that have been preserved in Iceland.

But why did someone show such a historic item so much disrespect as punching holes in it and make it into a simple utensil?

In an interview with The National Broadcasting Service Guðvarður Már Gunnlaugsson, an expert at the Árni Magnússon Institute, explained that when the contents of the old manuscripts had been copied on paper (starting in the 16th century) the old skin books were deemed redundant. The skin they were made of was, however, considered quite precious and often found an afterlife in different roles. Other examples include for example insoles of shoes and patterns for clothing.

The interesting fact is that this recycling of the old books played a large part of them being preserved instead of being thrown away.

The books were made of calf skin, a very expensive material indeed. Flateyjarbók the largest medieval Icelandic manuscript, includes 225 written and illustrated vellum leaves, made from the skin of 113 calves.

Read more: Where does the Icelandic language stem from?

The Icelandic sagas were written starting in the 13th century, even though the events described took place 200 to 300 years prior.